The significance of this discovery cannot be overstated, so what does it mean to be an archaeologist in the modern age? How do we go from identifying a ‘patch of dirt’ that may be of interest, to making a monumental discovery that forever changes our understanding of the world?

It might surprise you that the excavation and reconstruction of fossils involves technology developed for the International Space Station, as well as products available in every supermarket.

In the case of Homo erectus, we loosened the hardened rock using acetone (nail polish remover to you and me), which I had to suck up through a garden-variety straw. While this is the least invasive method of cleaning fragile and fractured bones, it has resulted in me ingesting a lot of dirt (as well as the occasional fossil rat bone).

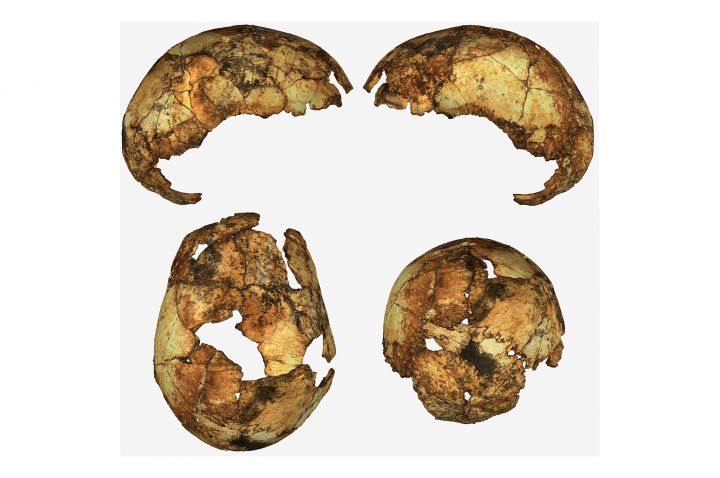

After weeks spent carefully cleaning and stabilising the hundreds of individual Homo erectus bones, so began the world’s hardest, but most rewarding, three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Once the tiny fragments were reunited after millions of years encased in stone, we were rewarded with a rare window into our ancestral past, a relic of a once living and breathing human relative.

In order to analyse the fossil and showcase it to the rest of the world, we used a high resolution 3D Artec Space Spider Scanner – developed to help astronauts at the International Space Station – to scan a copy of the now pieced-together cranium.

The fossil we now know as the DNH 134 Homo erectus cranium – also nicknamed Simon – was the first fossil reconstruction I had ever undertaken. I had joined the expedition in South Africa as part of my first field season with La Trobe.

When the hundreds of fragmentary bones were scooped up and placed in front of me, the expectation everyone had was that we were dealing with a badly damaged fossil baboon. No doubt still an interesting fossil, but not one to offer that rare glimpse into human evolutionary history that archaeologists are always striving to find.

To contextualise the rarity of these types of fossils, consider that while there are hundreds of baboon fossils at the site we were working on, the entire fossil collection documenting human evolutionary history could comfortably fit into the back of a ute. Fossils of early Homo, our own genus, are even rarer.

After meticulous excavating, cleaning and reconstructing, I can clearly remember the moment when my colleague and I realised what we had been poking and prodding at for the last two weeks. We had in our hands an almost perfectly preserved cranium of a Homo erectus child, no more than three to six years of age, that disappeared into the cool and dark depths of a South African cave two million years ago.

Our studies following the discovery revealed this direct human ancestor is the world’s earliest known evidence of Homo erectus.

Archaeology and palaeoanthropology are disciplines that are driven by fieldwork in every far flung and remote corner of the world.

In 2020, we’ve had to adapt.

La Trobe University students across all disciplines are facing the challenges and opportunities that are posed by the necessary move to online learning. But what of disciplines like archaeology that ordinarily have such a large focus on fieldwork and practical experience?

While there is no perfect substitute for practical, real-world experience – like placing fossil casts and stone tools into the hands of students – La Trobe’s Department of Archaeology and History has developed novel solutions.

We’ve invested in a raft of cutting-edge 3D scanners to unite humanity’s most recent technological achievements with its most ancient. We’ve digitised our stone tool and fossil collections.

This innovative approach will allow archaeology students to learn about stone tools, human ancestral fossils, and a range of other material in 3D. As online lectures and tutorials temporarily replace face-to-face subject delivery, our ancient stone tool and fossil collections have also entered the digital age.

Our academic and teaching community have banded together to ensure that students can still learn about archaeology in a practical and immersive way. The shared goal of lecturers, tutors and students within the Department is to stay connected with one another and the discipline that we all love. Together, and with the excellent support being provided by the University, we will ensure 2020 is a rewarding, enjoyable, successful, and unique year for La Trobe’s archaeology students.

Whether you’re looking to become a researcher or academic, government heritage manager, private consultant or even a museum curator, find out more about La Trobe’s Bachelor of Archaeology.

Media are welcome to re-publish this article with attribution to Graduate Researcher Jesse Martin, La Trobe University.

Read more opinions and expertise from La Trobe academics here.