Back in 1921, the United States introduced immigration restrictions based on national quotas. The quotas were tightened in 1924, and again in 1929, and remained in place until 1965.

The restrictions were part of a racist program to close the borders to “undesirable” migrants, but they carried the pretence of being colour-blind. As a result, these quotas affected even Australia – a fellow “white man’s country” that proudly advertised its own White Australia policy and boasted of a 98% British population.

Australians of that era violently protested their restriction and the traumatising border detention that followed. Yet today’s Australians have been more than willing to subject refugees and asylum seekers to similar (or worse) treatment. There is also one key difference: Australian immigrants detained and deported in 1920s America were not admissible under US law, whereas it is perfectly legal to seek asylum.

From July 1921 Australia’s quota for US immigration came out at a measly 279, later reduced to 100 — far less than the tens of thousands allocated to more populous nations.

Prior to this point, white Australians had enjoyed a virtually unfettered right to roam the globe. As British subjects, who travelled on British passports, Anglo-Australians could move at will around the still vast British Empire. They also typically enjoyed a warm welcome in the States.

The situation was different for the small number of non-Anglo Australians, who faced many more restrictions on their mobility. Chinese-Australians, for example, had long been excluded from the US by virtue of their “Chinese race”.

Coming at a time when Anglo-Australians were used to crossing borders with ease, the US restrictions came as a shock. At first, they were effectively ignored, but it soon transpired that the quotas would be strictly enforced.

Within months, Australians who ventured to the States in excess of the quota were being detained and deported. In almost all cases, these were not shady underworld figures, but respectable citizens who had casually disregarded or misunderstood the new law. From late 1921, dozens of prosperous and even high-profile Australians would be locked up and expelled like hardened criminals.

Australians were incensed by this. Because they were white – and therefore “desirable” immigrants – they expected to be welcomed with open arms. When they were imprisoned instead, Australian newspaper headlines complained of “unfair treatment” and “innocent victims”.

Although Australians were in fact treated no worse – and often much better – than other restricted migrants, they assumed their racial privilege should place them above the law. As one Brisbane newspaper protested, Australia had been “ranked with such not wanted nations as Chinese, Japanese, Bulgarians and Turks”.

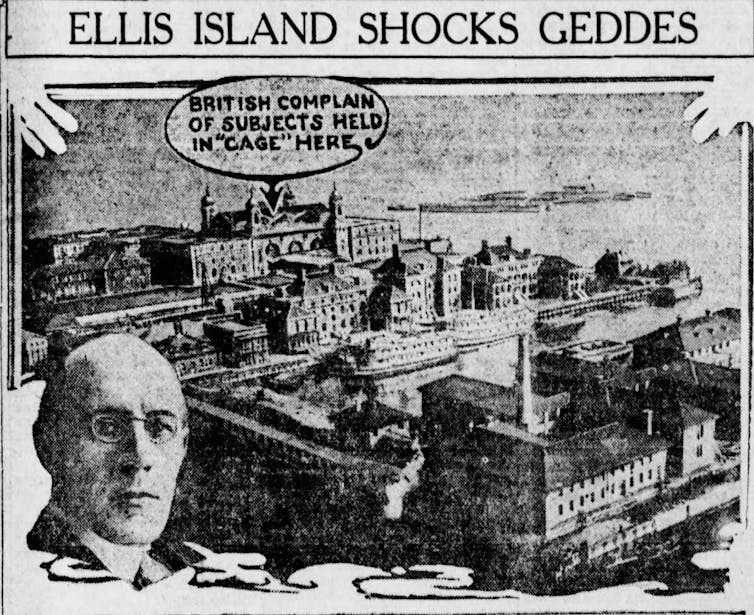

The horrors of Ellis Island

One of these Australian “illegal aliens” was Reginald Reynolds, who spent a week incarcerated on Ellis Island in 1922 after being detained on arrival in New York. Alongside 40 men “of all nationalities”, Reynolds spent the night in a dormitory with “doors and windows barred”. He was served “dry bread” for dinner, and awoke covered in flea bites.

As a prosperous white man accustomed to deference, Reynolds did not take his detention lightly. He sent word to family in London, who complained to the US consul and Australian high commissioner. A graphic letter detailing the “Horrors of Ellis Island” was syndicated in the Australian and New Zealand press. “Here in New York we get treated like so many dogs,” Reynolds told his fellow Australasians.

Reynolds’ concerns were shared by his compatriots detained on Angel Island, the immigration station in San Francisco Bay. The detention facilities were so primitive that one group of Australians renamed the site “Devil’s Island”. Babies were dying in dormitories, overcrowding was rife, and white detainees experienced the perceived insult of eating and sleeping alongside people of colour.

As objections to Australians’ detention mounted, politicians took up the matter in federal parliament. The Commonwealth government launched a formal investigation.

Over in New York, protesters gathered in the city’s Australian Church. Business also got involved: the LA Chamber of Commerce and San Francisco Foreign Trade Club urged their government to revise its tough stance, as Australian business leaders threatened a trade boycott.

Officials in Washington, however, refused to acknowledge any wrongdoing. Terse letters crisscrossed the Pacific. The episode climaxed in a heated exchange between the Melbourne-based US consul-general and the Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes, in late 1922. Although Hughes demanded an end to the “hardships” and “incovenience” faced by Australians, the consul-general, Thomas Sammons, stood firm.

Injustices ignored

When Americans ignored these cries of injustice, Australia turned to the mother country for support. For years, the Commonwealth government fed the British Foreign Office a litany of complaints that were forwarded to the US State Department.

Some Australian detainees even likened the detention facilities to a “concentration camp” — a claim that anticipated the current discourse around offshore detention.

By this point, the US immigration commissioner, W.W. Husband, had lost patience with Australian grievances. In his view, the average Australian was an arrogant scofflaw, who believed that white skin was “sufficient to set aside the law of any nation he might favour with a visit”, and felt “entitled to be treated as an American citizen as soon as he reaches the United States”.

Husband’s reprimand did little to quiet the chorus of complaint. By 1937, Australian resentment over US immigration policy was so notorious that it provided inspiration for Hollywood. When You’re in Love, a Columbia film starring Cary Grant and Grace Moore, is the story of an Australian opera star who, after being expelled from the US, buys a sham marriage to a US citizen to obtain American residency rights and circumvent the infamous quota law.

Last century, Australian “illegals” vehemently objected to being “penned like animals” in conditions that resembled “concentration camps”. Why, then, do we now think it’s acceptable to subject refugees and asylum seekers to much the same fate?

![]() If the likes of Reginald Reynolds felt dehumanised by mere days behind bars, maybe their descendants should spare a thought for the detainees who’ve spent years on Manus and Nauru.

If the likes of Reginald Reynolds felt dehumanised by mere days behind bars, maybe their descendants should spare a thought for the detainees who’ve spent years on Manus and Nauru.

Anne Rees, David Myers Research Fellow, La Trobe University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.