The offending ad showed a black woman appearing to turn white after using its body lotion. This online campaign was swiftly removed but had already hurtled through social media after a US makeup artist, Naomi Blake (Naythemua), posted her dismay on Facebook, calling the ad “tone deaf”.

Dove responded initially via Twitter.

The company then followed up with a longer statement: “As a part of a campaign for Dove body wash, a three-second video clip was posted to the US Facebook page … It did not represent the diversity of real beauty which is something Dove is passionate about and is core to our beliefs, and it should not have happened.”

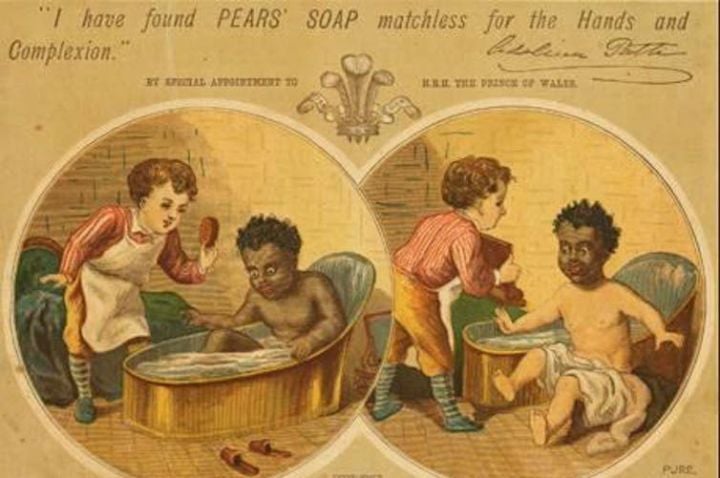

One has to ask, were the boys destined for Dove marketing kicking on at the pub instead of going to their History of Advertising lecture, the one with the 1884 Pears’ soap ad powerpoint? Jokes aside, Dove’s troubling ad buys into a racist history of seeing white skin as clean, and black skin as something to be cleansed.

Racist history

Dove has missed the mark before. In a 2011 ad, three progressively paler-skinned women stand in towels under two boards labelled “Before” and “After”, implying transitioning to lighter skin was the luminous beauty promise of Dove (Dove responded that all three women represented the “after” image).

Many of the indignant comments reference the longstanding trope of black babies and women scrubbed white. Australia has particular form on this front. Gamilaraay Yuwaalaraay historian Frances Peters–Little (filmmaker and performing artist) has demanded an apology from Dove. She posted a soap advertisement for Nulla Nulla soap from 1901 on Facebook to show the long reach of racism through entrenched tropes still at work in the Dove ads.

Wiradjuri author Kathleen Jackson has also written about the Nulla Nulla ad and the kingplate, a badge of honour given by white settlers to Aboriginal people, labelled “DIRT”. She explains that whiteness was seen as purity, while blackness was seen as filth, something that colonialists were charged to expunge from the face of the Earth. Advertising suggested imperial soap had the power to eradicate indigeneity.

This coincided with policies that were expressly aimed at eliminating the “native”. In Australia the policy of assimilation was based on the entirely spurious scientific whimsy of “biological absorption”, that dark skin and indigenous features could be eliminated through “breeding out the colour”.

In New South Wales, “half-caste” girls were targeted for removal from their families and placed as domestic servants in white homes where it was assumed “lower-class” white men would marry them. These women were often vulnerable to sexual violence. Any resulting children, however begotten, would be fairer-skinned, due implicitly to the bleaching properties of white men’s semen.

Aboriginal mothers were vilified as unhygienic and neglectful. In fact, they battled against often impossible privation to turn their children out immaculately in the hope police would have less cause to remove them.

Real beauty?

Cleanliness and godliness, whiteness and maternal competency: these are the lacerations Dove liberally salted with its history-blind ad. It unwittingly strikes at the resistance and resilience of Aboriginal families who for generations fended off fragmentation, draconian administration and intrusive surveillance by state administrators. Its myopic implied characterisation of beauty as resulting from shedding blackness is mystifying.

In 2004, Dove kicked off a campaign for “Real Beauty”. It proclaims itself “an agent of change to educate and inspire girls on a wider definition of beauty and to make them feel more confident about themselves”. Dove’s online short films about beauty standards – including Daughters, Onslaught, Amy and Evolution – have been recognised with international advertising awards.

Yet Dove also sits in Unilever with Fair and Lovely, a skin whitening product and brand developed in India in 1975. This corporate cousin to Dove touts its bleaching agent as the No. 1 “fairness cream” and purports to work through activating “the Fair and Lovely vitamin system to give radiant even toned skin”. It is sold in over 40 countries.

Skin whitening products (there is also a Fair and Handsome for men, not associated with Unilever) are popular in Asia, where more than 60 companies compete in a market estimated at US$18 billion. They enforce social hierarchies around caste and ethnicity. Since the 1920s the racialised politics of skin lightening have spread around the globe as consumer capitalism reached into China, India and South Africa.

Dove responded to its controversial ad by saying that “the diversity of real beauty… is core to our beliefs”. But “core” here seems skin-deep when it fails to penetrate into the pores of its parent company and its subsidiaries.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.