These words, published in the Mount Alexander Mail in 1856, were penned by a settler woman struggling to support her family in a white man’s world. She was a British born woman of the African diaspora, a single mother of four and restaurateur living in Castlemaine. Her name was Fanny Finch, and it is our duty to know her story.

She arrived on Dja Dja Wurrung country, the Forest Creek diggings, in 1852 and was described by a contemporary as “the first woman on the diggings”. Before education was mandatory and government funded, Fanny prioritised and paid for her children’s education, purchased land in Castlemaine, and financially contributed to the hospital.

In 1863, at 48 years of age, her death notice described her as a woman who possessed “a genuine tenderness of heart, ready to serve another in distress and that too, without the slightest ostentation”. She was a woman of significant achievement.

It doesn’t end there.

Six months before Fanny Finch wrote to the Mount Alexander Mail she turned up at the Hall of Castlemaine, now the Theatre Royal, and cast a vote in the local municipal elections. This means one of the first women to vote in Victoria was of African descent.

Fanny had left an abusive husband to pave her own way in life. This was exceptionally courageous at that time because single mothers, especially women of colour, were among the most stigmatised of settler society. This decision led Fanny to make even greater sacrifices.

Alongside her restaurant business, Fanny also engaged with sex work. This was one the few trades in which women could earn a liveable wage; ironically, however, it was also highly demonised and dangerous. Fanny was constantly fighting for her right to live in safety, let alone earn a living against the oppressive racial and gendered forces stacked against women, especially Indigenous women.

As we mark International Women’s Day, Fanny’s story is an enduring reminder that women’s struggles, achievements and privileges exist within complex contexts, and their determination to resist oppression spans time. All we need to do is listen.

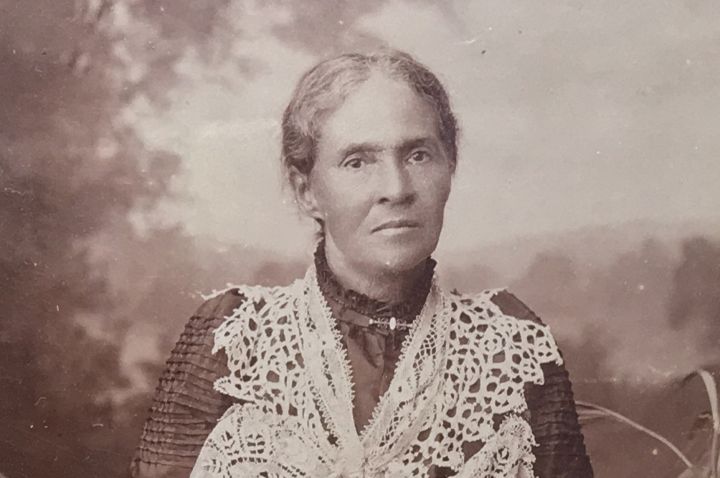

Caption: Fanny’s eldest daughter, Frances Cecilia Grenville (nee Finch) c.1895. From a private family collection.

First published in Australian Community Media.