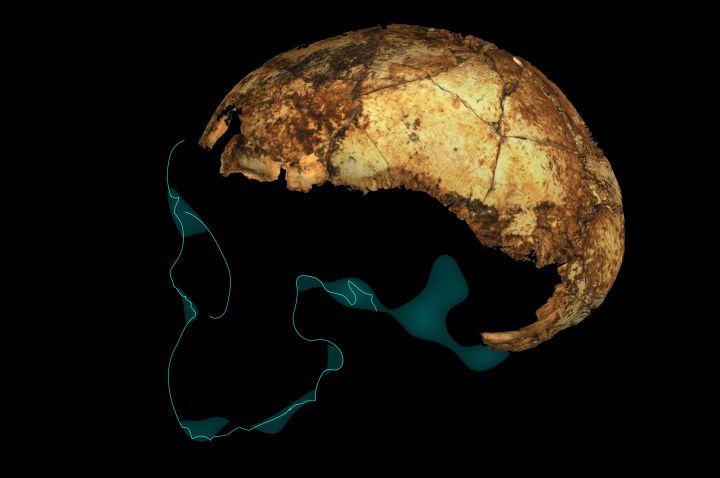

The two-million-year-old fossil was reconstructed from more than 150 individual fragments excavated in South Africa over a five-year period.

Published today in Science, the findings are part of an international research excavation in the fossil-rich Drimolen cave system north of Johannesburg.

Project director and lead researcher Professor Andy Herries – Head of La Trobe’s Department of Archaeology and History – said the age of the DNH 134 fossil shows that Homo erectus existed 100,000 to 200,000 years earlier than previously thought.

“The Homo erectus skull we found, likely aged between two and three years old when it died, shows its brain was only slightly smaller than other examples of adult Homo erectus,” Professor Herries said.

“It samples a part of human evolutionary history when our ancestors were walking fully upright, making stone tools, starting to emigrate out of Africa, but before they had developed large brains.”

La Trobe PhD student and paper co-author Jesse Martin, who reconstructed the cranium, said that the newly discovered fossil demonstrates that Homo erectus, our direct ancestor, clearly evolved in Africa

Professor Herries said that unlike the world today, where we are the only human species, two million years ago our direct ancestor was not alone.

“We can now say Homo erectus shared the landscape with two other types of humans in South Africa, Paranthropus and Australopithecus. This suggests that one of these other human species, Australopithecus sediba, may not have been the direct ancestor of Homo erectus, or us, as previously hypothesised.”

La Trobe PhD student and paper co-author Angeline Leece, who analysed the human fossils, said the new crania offered an unparalleled insight into how three different human species, with quite different adaptations, shared a changing environment together.

Paper co-author Dr Justin Adams, from Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute, said the discovery raises some intriguing questions about how these three unique species lived and survived on the landscape.

“One of the questions that interests us is what role changing habitats, resources, and the unique biological adaptations of early Homo erectus may have played in the eventual extinction of Australopithecus sediba in South Africa,” Dr Adams said.

“Similar trends are also seen in other mammal species at this time. For example, there are more than one species of false sabre tooth cat, Dinofelis, at the site – one of which became extinct after two million years. Our data reinforces the fact that South Africa represented a truly unique mixture of evolutionary lineages – a blended community of ancient and modern mammal species that was transitioning as climates and ecosystems changed.”

Co-director of the Drimolen excavation project, University of Johannesburg PhD student Stephanie Baker, said the discovery of the earliest Homo erectus marks an incredible milestone for South African fossil heritage.

“Not only does the research illustrate the importance of South Africa in the human story, but this project is the first major breakthrough in hominin research with a female, South African director,” Ms Baker said.

“The story of hominin evolution is once again changing, but importantly for us locals, so is the field.”

Professor Herries said Homo erectus marks the beginning of an adaptable species researchers now recognise as the origin of our ancestors becoming more human-like.

“However, as the last surviving human species, we should not think we are immune to the same fate as Australopithecus, who likely became extinct as a result of the changing climate two million years ago.”

Media Contact: Dragana Mrkaja – 0447 508 171 – d.mrkaja@latrobe.edu.au