William Shakespeare died more than 400 years ago, in 1616. The famous collected edition of his plays, now known as the ‘First Folio’, appeared seven years later. Today, as we approach the quatercentenary of that edition, Shakespeare’s popularity and influence are assured. His plays continue to attract audiences. They are unshakeable mainstays of school and community theatre programs. There are Shakespearean films and television series. Shakespearean books are highly valued. (In April this year, Christie’s New York will sell a copy of the First Folio; the estimated sale price is US$4 million to US$6 million.) And there is vibrant research interest in Shakespeare and his world – so much so that we are in a golden era of Shakespearean scholarship and discoveries. (Just one example: the discovery in 2019 of John Milton’s annotations in a copy of the First Folio drew worldwide attention.)

Much of the research interest in Shakespeare has focused on his own collection of books and manuscripts. From textual analysis of his plays and poems, we know he drew extensively from prior works, and we know, with a high degree of confidence, what those works were. They include histories, novels and earlier poems and plays. Though Shakespeare’s library has been dispersed, and solid evidence of Shakespearean provenance is scarce, we can infer that he likely owned some of the sourcebooks that he used in his work. He probably also kept manuscripts and playscripts, and he may have owned editions of his own works that were published in his lifetime. No documents from Shakespeare’s lifetime refer to his library, but his plays and poems frequently speak of books and their production; and documents from after his death refer to his former home containing a study with books.

That home was ‘New Place’, a fine building in the Warwickshire town of Stratford-upon-Avon. Shakespeare was born in Stratford, and he died there, too. In 1597, he bought New Place for more than £60. Susanna Hall, Shakespeare’s eldest child, married Dr John Hall. After Shakespeare’s death in 1616, Susanna and John lived at New Place with Shakespeare’s widow, Anne (until her death in 1623). Much of what we know about Shakespeare and his family comes from legal papers and real estate documents: court notices, judgements, wills, leases and records of dealing in property. The evidence that there were books at New Place comes from a fascinating legal dispute that involved Susanna and her son-in-law, Thomas Nash.

Baldwin Brookes was a mercer and prominent citizen of Stratford-upon-Avon. In 1635, he obtained a judgement in the Court of King’s Bench against John Hall for payment of a debt of £77.13s.4d. But Hall died later that year, before the debt was settled. (Hall’s will lists his possessions including a ‘study of books’, to be disposed of by Thomas Nash.) Brookes therefore took legal aim at Susanna. On 14 February 1636, he filed a ‘bill of complaint’ against ‘Susan Hall, widow’, claiming excessive delay in closing the estate and settling the debt. The formal legal response, dated 5 May 1637, from Susanna and her son-in-law, gives details of the family’s properties in Stratford and London, ‘given to her the said Susan by the last will and testament of Willm Shackspeare gent’.

On 12 May 1637, Susanna Hall countered in the Court of Chancery with her own bill of complaint against Brookes, claiming ‘execution had already been levied’. In August 1636, Brookes, with the assistance of the Undersheriff and some bailiffs, had forced his way into New Place, and removed from there ‘divers books boxes deskes monyes bondes bills and other goodes of great value’. These movable assets – the ‘money, books, goods, and chattels of…John Hall deceased’ – were stated to be ‘to the value of £1000’. But Brookes and the Undersheriff and the bailiffs were accused of handling the recovered assets sloppily and recklessly; after making their forced entry, they had ‘converted the same to their or some of their own uses without inventorying or appraising the same’. Here the legal paper-trail goes quiet. Whether the plunder was recovered is unknown.

In the last two decades of his life, Shakespeare had styled himself as a ‘gentleman’, and in support of this he was the prime mover behind an official application to recognise the Shakespeare family coat of arms. Early in the seventeenth century, the fashion among gentleman and gentlewoman book-owners was to have their volumes finely bound in leather decorated in gold, sometimes with the owner’s mark or arms. The idea that Shakespeare had his books bound in this way is enticing, but so far no one has found a Shakespearean binding. There are, however, some fascinating candidates.

In Washington’s Folger Shakespeare Library there is a theological work: Agostino Tornielli’s Annales sacri ab orbe condito ad ipsum Christi Passione reparatum cum praecipuis ethnicorum temporibus apte ordinateque dispositi. The book was published in Milan in 1610, then shipped to England where, in 1615, it was bound in brown calfskin in a distinctive style.

The book’s spine is divided by raised bands into eight compartments decorated with golden sprays of laurel. The cover panels feature a rectangular decoration with, in the centre, an image blocked in gilt showing the tragic story, from Ovid and used by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, of Pyramus and Thisbe. (The story also influenced Romeo and Juliet.) In the image, Pyramus lies on the ground, expired, and Thisbe ends her own life by spearing herself on an upright sword. A lion flees but Cupid stays to watch the spectacle. Apart from the handsome leather cover, the edges of the text-block are beautifully decorated with elaborate patterning: snail and lion motifs within laurel wreaths on a field of gilt ‘fleurons’, or printers’ flowers. (Shakespeare’s Library.)

Henry Folger acquired the book in 1927 from the booksellers Maggs, who bought it from a Sotheby’s sale on 22 November 1926 (lot 269). It seems that Henry Folger was mainly interested in the Shakespearean connotations of the gilt block. (A pencil note on the book’s front pastedown reads, ‘With Illustration in gold on cover of Pyramus & Thisbe’.) Three other bindings with the Pyramus and Thisbe block have also been documented: one on a copy of Ben Jonson's Workes, 1616, and the others on books published in 1541 and 1600. All four volumes date from before the year of Shakespeare’s death, except for the Jonson one, which dates from that year.

Little is known about the four volumes’ early provenance. Who was the wealthy book-lover who, early in the seventeenth century, had the books bound with a fine gold motif and other deluxe decoration including handsome gauffered edges? The presence of the Pyramus and Thisbe motif on a volume of Jonson’s Workes (1616) deepens the Shakespearean connections. Jonson’s book is closely associated with Shakespeare. Among other things, it served as a model for Shakespeare’s First Folio, a volume for which Johnson contributed commendatory verses. Jonson's folio names Shakespeare as a principal player for ‘Every Man in his Humour’ and ‘Sejanus’. It is notable that Jonson’s folio included plays written for the commercial theatre: ‘This marked a crucial step in establishing the literary credentials of the public theatre, which was often dismissed as ephemeral at the time; one contemporary responded to the publication with a distich: “Pray tell me Ben, where does the mystery lurk / What others call a play, you call a work?”’

(At the State Library of NSW, I recently had the chance to see simultaneously a Shakespeare First Folio and a Jonson First Folio. Though the books were issued seven years apart and by different publishers, editorially and typographically they bear a strong family resemblance. Jonson played a significant role in the marketing and promotion of Shakespeare’s First Folio, and he may have helped edit the plays and steer their publication, just as he had done with his own Workes.)

In 2015, Sotheby’s New York offered the Jonson ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ volume as part of the Robert S. Pirie sale. The book’s pre-auction estimate was US$80,000 to US$120,000 but it sold for the rich price of US$250,000. The auction catalogue described the binding as follows: ‘Contemporary black turkey morocco, the covers panelled in gilt with elaborate gilt-tooled corner-pieces and with a central medallion of Pyramus and Thisbe, smooth spine panelled in gilt with interlacing foliate wreaths, plain endpapers, gilt edges; ribbon ties lost, spine faded, extremities lightly rubbed.’

Provenance: J. B. Plowman — Britwell Court Library (Sotheby’s London, 8 February 1922, lot 397) — Templeton Crocker. acquisition: Seven Gables, 1959. The splendid binding is one of a handful known with the centerpiece depicting the legend of Pyramus and Thisbe, the ill-fated lovers from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. (The stamp was misidentified in the Britwell Court catalogue as representing Lucretia falling on a sword.) On the trunk of the tree in the medallion are the initials IS with a key, but it is not clear if they are the cipher of a designer, toolcutter, bookseller, or binder.

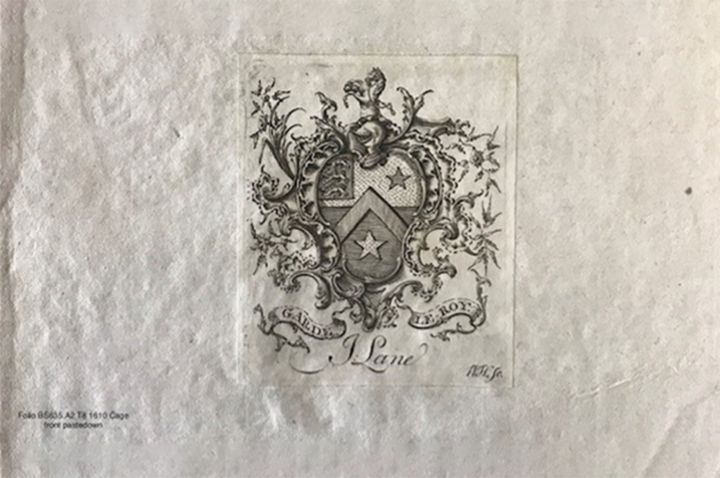

The Folger’s Tornielli volume features the heraldic bookplate of ‘J. Lane’. The bookplate artist is identified as ‘WH’. Those initials have variously been read as referring to William Hogarth and William Hibbart, but they probably belonged to William Henshaw.

The Lane bookplate adds a layer of intrigue to the book’s provenance, and takes the search for Shakespeare’s library in a fascinating direction.

After the execution of Charles I in 1649, the prince who would be Charles II left England, then returned with an army of 10,000 men. They met Cromwell’s forces and were defeated (3 September 1651). The prince fled, with Cromwell’s men in pursuit. Through good fortune, Charles came upon Colonel John Lane and other royalists, who protected him and made plans for his escape. (Lane’s father was Sir Thomas Lane, 1585–1660, and his mother was Anne Lane, née Bagot, 1589–1646, daughter of Sir Walter Bagot.)

Dressing him in humble clothes, they helped him evade the searching soldiers. To reach the sea and the prospect of finding a ship, Charles and Colonel Lane rode through the night. The next day, Charles met the colonel’s sister, Jane. She was enlisted into her brother’s plans, in which she was to play a major part. Pretending to be Jane’s servant, Charles adopted the name (‘William Jackson’) and the identity of a tenant farmer. On the journey to the coast (riding on ‘a strawberry roan horse’) there were narrow escapes, including encounters with men from both sides of the battle of 3 September. At Trent, Jane and others arranged for a boat that would carry Charles and his friend, Wilmot, to France. The thrilling escapade had a happy ending. From the coastal village of Charmouth, Charles and Wilmot made their escape.

There were consequences, though, for those who remained in England. Colonel Lane was imprisoned, as was his father. Jane Lane was suspected of also having aided Charles’s flight. Betrayed to the republican Council of State, she fled to France (in 1651), and Charles arranged for her to become a lady-in-waiting for his sister, Mary, in Holland. In June 1652, Charles wrote to Jane expressing his thanks and promising to prove his gratitude. After the Restoration in 1660, he gave Lady Jane a generous pension along with portraits of himself, a lock of his own hair, jewels, a fine snuff box and other valuable gifts. A large grant of land was made to the Lane family, and – in a spectacular and unusual demonstration of royal favour – the three Lions of England were added to the Lane coat of arms, for ‘the great and signal service performed by John Lane, Esq., of Bentley, in the county of Stafford, in his ready concurring to the preservation of King Charles II after the battle of Worcester.’

(Penguin Books was founded in 1935 by the three brothers – Richard, Allen and John Lane – who were related to the famous publisher, John Lane senior. The Lane brothers grew up hearing a family tradition that, because of the deeds of Jane and Colonel John Lane, their family had special rights to graze livestock on royal land.)

The augmentation of the Lane coat of arms is described in The Romance of Heraldry (London: Dent & Sons, 1929):

Mistress Lane’s courageous loyalty earned for her family one of the most notable augmentations known to heraldry, none other than the three lions of England. They were added as a canton to the Lane arms – a shield divided horizontally gold and blue, with a red chevron, and three stars counter-coloured.

As the King’s loyal protectors, the Lanes adopted the motto, ‘Garde le Roy’. Jane Lane married a baronet, Sir Clement Fisher, and died as Lady Jane Fisher at Packington Hall, near Birmingham, in 1689. (See her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.)

The J. Lane heraldic bookplate in the Folger includes the special features: the three royal lions, and the ‘Garde le Roy’ motto. Other examples of the bookplate are known. Brian North Lee, the great bookplate collector and scholar, owned one that was sold at the 6 December 2008 auction of items from his collection (and was correctly described there as by Henshaw). And remarkably, inside the Folger Library, there is another example – one that further deepens the Shakespearean connections of the Tornielli ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ volume.

This other Lane bookplate appears on one of the Folger’s greatest treasures: Folger Shakespeare First Folio copy no. 13 (red morocco, gilt edges; Lee, S. Census, 19; West, A. J. Shakespeare first folio, 71.) Said to be bound by Roger Payne, the volume was acquired by the Folgers and was formerly owned by the Earl of Gosford and the Buckley family. The catalogue entry reads in part:

Bookplate: “J: Lane. W[?]H [William Henshaw?] sc.” John Lane family library; Earls of Gosford-Abel Buckley/H.S. Buckley-Hargreaves copy.

Anthony James West’s 2003 census of First Folios gives the following details of the provenance of Folger copy 13:

Apparently purchased c.1660 by Col. John Lane, of Bentley Hall, Staffordshire, Charles II’s protector. Subsequently in possession of Col. Lane’s descendant, Col. John Lane, of King’s Bromley, whose book-plate designed by William Hogarth [sic.] is inserted [still there].

At the sale of the Lane library, Sotheby’s 82, 19 April 1856, it was purchased by Toovey, for £164 17s. (West SFF I, p. 93). It passed to Archibald Acheson (1806-64), MP, 3rd Earl of Gosford. His son, Archibald Brabazon Gosford (1841-1922), the present earl, disposed of it. The sale was in the father’s name, Puttick & Simpson 2673, 21 April 1884: the Folio was purchased by James Toovey for £470 (West SFF I, p. 95). It was soon afterwards sold through another bookseller [Nattali of Duke Street] to the present owner, who ‘paid £1,100 for it’.

The owner in Lee, Census, was Abel Buckley, Esq., Ryecroft Hall, [Audenshaw], near Manchester. A 1907 note in Maggs’s copy of Lee, Census, also states that Nattali sold the copy, ‘a few years ago’, to Abel Buckley for £1,100, adding (after an illegible word) ‘giving it to his son’. At the sale of the ‘Property of H. S. Buckley’, the Folio was sold, Sotheby’s 421, 31 May 1907, and was bought by Quaritch for £2,400 (West SFFI I, p. 109). Apparently, Folger saw it in London in August 1907 when Quaritch had it priced for £3,000; he noted it was sound and unwashed. Quaritch sold it in October 1907 for £2,850 to ‘Hargreaves’ (Quaritch records). The ‘Property of Colonel Hargreaves’ was sold, Sotheby’s 88, 11 July 1910, and the Folio was bought by Quaritch for £2,000 (West SFFI I, p. 110). Folger paid $10,200 for it in the same month.

The idea that the Tornielli volume and a First Folio were formerly in the same early collection is intriguing, though so far the Lane provenance and the connections between the two Folger volumes have not attracted significant research interest. They deserve further study and attention, as do other possible connections between the Lane family, Stratford-upon-Avon and the dispersal of Shakespeare’s library.

One circumstantial connection: on Charles II’s famous escape with Jane Lane, the disguised prince and his protectors passed through Stratford-upon-Avon. Other connections between Lanes and Stratford date from Shakespeare’s day, and have again reached us via legal and real estate documents. A John Lane, for example, leased property in Stratford in the sixteenth century, and Nicholas Lane, a wealthy Stratford man, sued William’s Shakespeare’s father, John Shakespeare, in 1587. A more famous dispute between Shakespeares and Lanes took place in 1613.

According to legal records, litigious Susanna Hall sued a Lane after he made a serious accusation. Specifically, John Lane, aged 23, accused Susanna of adultery with Rafe (Ralph) Smith, a 35-year-old haberdasher. Lane said Hall ‘had the running of the reins’ (venereal disease), and claimed she had caught it from Smith, and possibly from John Palmer. There has been speculation that Lane’s accusation was politically motivated. Others have attributed it to drink. Whatever the cause, the Halls sued for slander. When the matter came to court, Lane did not appear. In his absence he was found guilty and excommunicated.

See also:

https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/blogs/is-all-of-this-true/.

There were other connections, too, between Lanes and Shakespeares. John Lane’s sister Margaret, for example, married John Greene, who was described as ‘Shakespeare’s kinsman’.

Let us take stock. The ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ binding links the Folger Tornielli volume to a copy of Ben Jonson’s folio and to other volumes from Shakespeare’s day. The J. Lane bookplate, by Henshaw, links the Tornielli volume to a copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio and to an early owner who had royal connections. This sparks an intriguing thought. Were the ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ volumes once part of a royal treasure, on account of their fine bindings and significant provenance? Could they even have been part of the royal bounty gifted to the Lanes? And then there are the books at New Place in Stratford. Did someone take those books away, after they were seized by the Undersheriff and bailiffs? Another line of inquiry (even more speculative) concerns the potentially Roman Catholic connections of Shakespeare and the books. Late in the seventeenth century, the Anglican clergyman Richard Davies made a private note about Shakespeare, ‘He died a papist’. Another fascinating discovery is a Catholic ‘will’, now lost, that reportedly bore the name of Shakespeare’s father. Were the Shakespeares secretly recusant Catholics? After William Shakespeare’s death, did people protect his ‘Catholic’ books from the Puritans, and would that explain the Tornielli volume?

The search for Shakespearean evidence has involved much legwork and eyework. Scouring official archives; old and new library catalogues; book auction catalogues and booksellers’ catalogues; wills and other legal documents from Shakespeare’s day; and scrutinising public and private collections around the world, including the major Shakespeare holdings in London, Oxford, Tokyo, Washington and New York. The ‘meta-search’ involves studying prior searches for Shakespeare’s library, including ones conducted in the eighteenth century; and studying documentary databases and censuses, including the indispensable ‘Shakespeare Documented’; generations of censuses of copies of the Shakespeare First Folio; databases of non-folio Shakespeare editions from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; and searches for editions of plays by Shakespeare’s contemporaries. (People have also searched for physical relics, including Shakespeare’s skull, said to be missing from the chancel of the Holy Trinity Church.)

In more ways than one, digital communications are aiding the search. Every week, for example, I receive dozens of emails from booksellers with book offers (not all Shakespearean). And every few months I receive emails from people with Shakespearean discoveries: artefacts; possible inscriptions; a code purportedly buried in the Sonnets’ dedication... As the discovery of Milton’s First Folio annotations showed, there is a vibrant twitter conversation about Shakespeare. Theories and discoveries are shared across overlapping networks of orthodox and unorthodox scholars. Other modern tools, too, are being used in the search, including DNA, in the expanding field of ‘biocodicology’, which has turned library dust into data. And of course there is eBay.

Where is all this searching leading us? We are building a better understanding of Shakespeare, his authorial achievement, early modern print culture, and early modern book ownership. And we are on a treasure hunt.

PHOTO: Folger Shakespeare Library