Late in the seventeenth century, Margaret Douglas was born into a distinguished Scottish military family. In November 1720, at the age of 26, she married Adam Smith, a prominent lawyer and customs official. Adam was 14 years her senior and had been married before. In 1723, Margaret was pregnant when her husband died, at the age of just 43. A few months later, Margaret’s baby was born. She gave him his father’s name.

The younger Adam Smith’s fatherless upbringing would receive much attention from biographers, as would the following incident. In 1726 or thereabouts, Margaret and her three-year-old son were visiting the Douglas family seat at Strathenry, north of Edinburgh. The little boy was playing alone near the front door – and then suddenly he wasn’t. Perhaps he’d wandered off. Or maybe something more sinister had happened. The boy’s absence was soon noticed. People set off in pursuit. They tracked him down, and he was soon back with his mother.

The early Smith biographies (and Smith’s newspaper obituaries) characterise the incident as an abduction. Dugald Smith’s 1793 Account of the Life and Writings of Adam Smith, for example, pictures the boy at the home of his uncle, when he is taken away by ‘that set of vagrants, who are known in Scotland by the name of Tinkers’. After the boy is snatched, according to the Account, Adam’s uncle sets off with helpers and overtakes the ‘vagrants’ in nearby Leslie wood.

In William Draper’s 1830 Life of Adam Smith, the abductors are ‘a party of gypsies’, so named because they were erroneously thought to have come from Egypt. Haldane’s 1887 Life has the child at the house not of his uncle but his grandfather who, having conjectured what might have become of the missing boy, makes a ‘vigorous pursuit’.

John Rae’s 1895 version of the story contains several dramatic elaborations and extrapolations. Smith, ‘in his fourth year’, is stolen by ‘a passing band of gypsies’ and momentarily cannot be found.

But presently a gentleman arrived who had met a gipsy women a few miles down the road carrying a child that was crying piteously. Scouts were immediately despatched in the direction indicated, and they came upon the woman in Leslie wood. As soon as she saw them she threw her burden down and escaped, and the child was brought back to his mother.

What are we to make of all this? Though retellings of the incident would appear in all subsequent major Smith biographies, there’s still a lot we don’t know. Was Smith really abducted? And if so, were the kidnappers really gypsies or tinkers or something else? And what exactly were their intentions?

***

There is much to dislike in the abduction story. The Douglases had a big house and it would have been a big deal to steal a child from its front door. A more likely explanation is that he wandered off, and came into the company of the so-called tinkers by chance. In Smith’s adulthood, his absentmindedness would become a defining trait. During a visit to a tannery, for example, he walked the plank over a tanning pit. Expounding on the division of labour, he forgot he was on precarious ground and ‘plunged headlong into the nauseous pool’. John Rae’s 1895 account of the ‘abduction’ ends with a dig at Smith’s absentmindedness: ‘He would have made, I fear, a poor gipsy.’

If the tinkers were innocent of the charges of abduction, that would explain why Smith’s trail was so easy to follow, and why the purported kidnappers evidently let him go so readily. But Smith’s family can be forgiven for thinking the worst. There was much suspicion at the time about vagabonds and vagrants, and fears about kidnapping were very much in the zeitgeist.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, economic abduction was a fact of everyday life in Britain. A parade of scoundrels pursued a variety of human targets. Nascent sailors could be shanghaied. ‘Child-strippers’ could steal children for their clothes. Girls could be kidnapped by brothel-keepers and other reprehensible characters. And all manner of abductees could be grabbed and sold into slavery.

‘Corsairs’ or ‘Barbary pirates’ raided coastal settlements in Ireland and south-western England. Large numbers of people were taken away in this fashion. In 1631, nearly all the inhabitants of the Irish village of Baltimore were kidnapped in a Barbary raid. Samuel Pepys’s diary describes his 1661 encounter with a Captain Mootham and Mr Dawes, both of whom had been taken into slavery in Algier to perform sundry manual and personal duties. Another kidnapping story was especially sensational. The mysterious disappearance of William Harrison gripped imaginations throughout the British isles.

***

On 16 August 1660, seventy-year-old Harrison left his home in the pretty market town of Chipping Campden, intending to walk to nearby Charingworth. When he failed to return, his wife sent his manservant John Perry to look for him. Next morning, Harrison’s son joined the search. On his way to Charingworth he met Perry, who said he’d not been able to find his master. But on the road between Chipping Campden and Ebrington, items of Harrison’s clothing were found. The man’s hat had been slashed and his shirt and neckband were covered in blood. Otherwise there was no sign of him, living or dead.

John Perry now said his mother, Joan, and his brother, Richard, had killed Harrison and hidden his corpse. Joan and Richard professed their innocence, but John claimed they’d dumped the body in a millpond. The pond was dredged, no body was discovered, but a jury found the three Perrys guilty of murder. They were hanged on Broadway Hill in Gloucestershire.

Things couldn’t get any worse for the Perrys – or could they? To universal astonishment, William Harrison reappeared with a colourful tale. He’d been abducted, he claimed, and taken to Kent and then by ship to Turkey where he was enslaved. More than a year later, according to Harrison, he escaped and stowed away on a Portuguese ship, returning to Dover via Lisbon.

Under the title ‘The Campden Wonder’, the story was published in popular pamphlet editions in 1676 and 1710, and in later editions of the Harleian Miscellany. The story was still a sensation at the time of Adam Smith’s birth. Over the following three centuries, people would try to make sense of the Campden Wonder. Harrison’s story attracted legitimate disbelief: the alleged abduction happened a long way inland, for example, and Harrison was old and wounded. Just as Smith would have made a poor gypsy, Harrison would have made a poor slave.

The labels ‘gypsy’ and ‘tinker’ have long been used with disparagement but not precision. Convenient scapegoats, the tinkers who were accused of taking Adam Smith may have been Irish Travellers. The origins of the Travelers are unclear. Now a recognised ethnic community, they’ve been linked to a nomadic way of life that pre-dates Celtic Britain. Other origin theories trace them to displaced aristocrats.

In the Travellers’ language, people such as Smith are ‘buffers’: muggle-like figures not inducted into the Travellers’ ways. The abduction incident is biographically powerful because of its emotional impact – there is the terror of what might’ve been – but also because it fits so well into Smith’s life and scholarship. In several important ways, the tinkers are his antithesis.

Symbolically rich, the labels ‘tinker’ and ‘gypsy’ are associated with a life of nomadism, superstition and low productivity – the exact opposite of the settled, rational, commercial world with which we associate Smith. (The Scottish enlightenment, in which he was a leading thinker, was an explicit reaction against superstition and magic. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith called science ‘the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition’.)

Whatever its cause, the incident was a dangerous near miss and a natural source of worry for his family, and for Smith himself. The incident places him in a tradition of famous kidnappings that includes the Getty and Hearst abductions, and the recent spate of ‘bossnappings’ in France. It also affected his life and legacy. The ‘invisible hand’ of the abductor reaches through Smith’s biography. It may have affected how he lived and worked, what he thought and believed, and how his ideas and beliefs were received.

Some hints about the impact can be gleaned from his lifestyle and wellbeing. During an unhappy period of study at Oxford, he seems to have entered a deep depression, one that he sought to cure by consuming large amounts of tar water. His mature years were punctuated by episodes of what some writers have called hypochondria. The amount of time he spent in quiet and focused work led David Hume to call him a sedentary recluse.

There are hints, too, in the examples he used in his writings. Before Smith, philosophers such as Lord Shaftsbury adopted a turgid style full of metaphorical obscurity. Smith in contrast used simple metaphors and everyday examples, so much so that they were noticed as a crucial and striking aspect of his work. In a letter thanking Smith for a copy of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Edmund Burke praised the ‘easy happy illustrations from common life and manners in which your work abounds’. After the publication of The Wealth of Nations, Hume wrote that the book was ‘so much illustrated by curious facts, that it must at last take the public attention’.

One aspect of Smith’s use of metaphor is particularly striking. He drew many of his examples from the fringes of society. He wrote of witches, beggars, paupers, thieves, slaves and sex workers. And he adopted a para-legal vocabulary, searching for the ‘laws’ of economics that would be analogous to the laws of physics and that would confer on the new discipline of political economy the same authority that physics enjoyed.

A case study in human nature and human failings, the ‘abduction’ may have affected Smith’s ideas about how people should live and what makes a good society. On economic as well as moral grounds, he opposed the trade in people. His major writings are full of references to slavery and the abuses to which it led. In other ways, too, he had progressive views. In considering the economic and legal causes of theft, for example, he was ahead of his time.

A large part of the economic gains of that time arose from extending the rule of law. In The Enlightened Economy, Joel Mokyr writes of how Smithian economic growth depended on the institutions that eliminated piracy, restrained highwaymen, and improved enforcement of contracts and property rights. Throughout recorded history, ‘predators, pirates and parasites’ were the arch enemies of growth. Smith’s world view and economic system depended on the extension and enforcement of laws, including those of personal protection.

(Described as a ‘tragic intellectual of the Baltimore underworld’, Russell ‘Stringer’ Belt was a principal character in the TV crime series ‘The Wire’. In a key episode, Bell lies murdered on the floor of his home. A detective finds a copy of The Wealth of Nations in the gangster’s bookshelf. ‘Who in f--- was I chasing?’ the detective gravely asks.)

Smith criticised not just slavery and highwaymen but crony capitalism, corruption, poverty, monopolies and other forms of exploitation. According to Smith biographer James Buchan, ‘Smith’s strongest characteristic, after his hypochondria and solitude, was probably his concern for the poorest sections of society’. In 1891, Carl Menger wrote that ‘Smith placed himself in all cases of conflict of interest between the strong and the weak, without exception on the side of the latter.’

Some of Smith’s analysis is wrongheaded (his work on ‘natural prices’ is an example) and more than one commentator has cast Smith as an economic bogeyman. Most, though, portray him as a gentle person and a thoughtful and humane writer. The impact of the abduction incident on Smith’s posthumous reception and reputation may have been as important as its impact on his life and work. By adding to the picture of an authentic and empathetic observer, the incident altered his authorial voice and heightened his intellectual influence. Readers sympathised with an author who’d once been a little boy in peril, and whose life might’ve been very different.

Smith’s likability continues to this day. Recent biographies and monographs are affectionate defences of him as a person as well as a thinker. The impact of his ideas will always be conjoined with a question: what would his legacy have been if his rescuers hadn’t found him in Leslie wood?

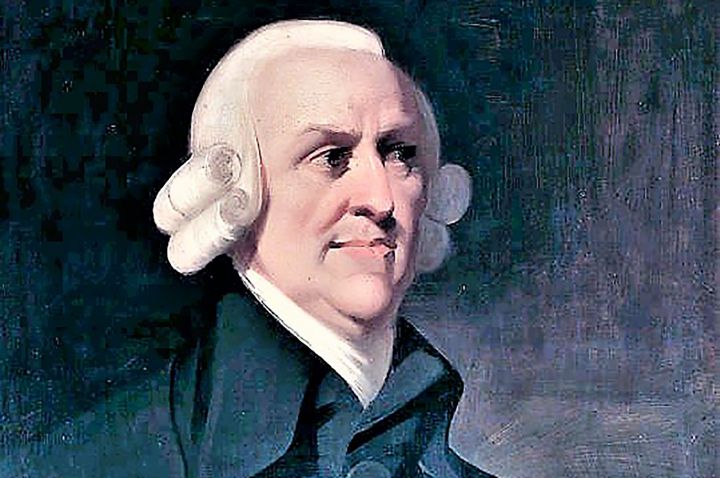

PHOTO: Wikicommons