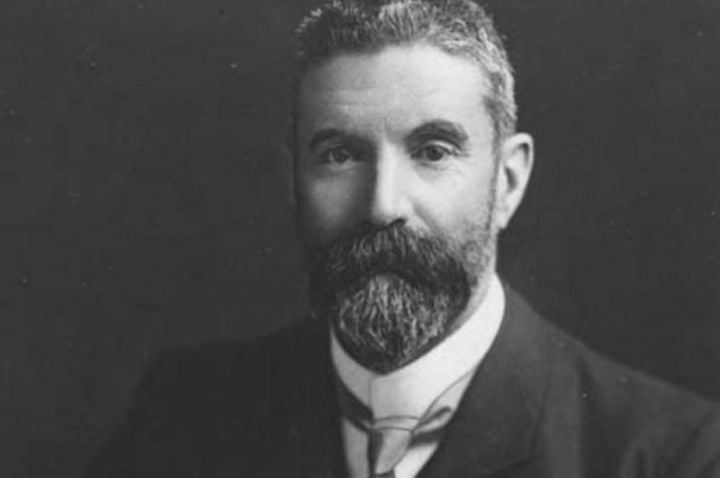

Australia’s federal Liberal Party began not with Robert Menzies in 1945, but with Alfred Deakin’s Commonwealth Liberal Party in 1909, and before that with his Liberal Protectionists.

As a leadership party, the Liberals have always needed heroes. But in the 1980s, as Liberals embraced deregulation, they turned against Deakin and the policies he championed.

In his brilliantly succinct description of Australian settlement, Paul Kelly identified the core policies of the early Commonwealth with Deakin, and compulsory arbitration and the basic wage with his Liberal colleague, Henry Bournes Higgins.

Deakin’s support for protection and for state paternalism were his key sins in the eyes of the Liberal Party as it rehabilitated the free-trade legacy of New South Wales Liberal premier George Reid. Reid is not a well-known figure, so this left the Liberals with only Robert Menzies for their hero, although he has now been joined by John Howard.

In jettisoning Deakin, the Liberals made a great mistake and showed the thinness of their historical memory. The party and its traditions did not begin with Menzies, but stretched back to the nation-building of the new Commonwealth, and into the optimism and democratic energies of the 19th-century settlers.

Indeed, Deakin was one of Menzies’ heroes. The Menzies family came from Ballarat, where Deakin was the local member, and his Cornish miner grandfather was a great fan.

Accepting his papers at the Australian National Library just before his retirement, Menzies described Deakin as “a remarkable man” who laid Australia’s foundational policies. It must be remembered that in 1965, Menzies supported all these policies the Liberals were later to discard.

When it came to choosing a name for the new non-labour party being formed from the wreckage of the United Australia Party, it was to the name of Deakin’s party that Menzies turned, so that the party would be identified as “a progressive party, willing to make experiments, in no sense reactionary”.

This is a direct invocation of Deakin and his rejection of those he called “the obstructionists”, the conservatives and nay-sayers, who put their energies into blocking progressive policies rather than pursuing positive initiatives of their own.

In June this year, Turnbull quoted these words of Menzies, in his struggle with the conservatives of the party. Clearly Turnbull wants to be a strong leader of a progressive party, rather than the front man for a shambolic do-nothing government. He does have some superficial resemblances to Deakin: he is super-smart, urbane, charming and a smooth talker who looks like a leader. But as we all now know, he lacks substance.

When I first began thinking about this piece I was going to call it “What Malcolm Turnbull could learn from Alfred Deakin”. But I fear it may now too late for him to save his government, and might be more accurately called “What Malcolm Turnbull might have learned from Alfred Deakin”.

First, he could learn the courage of his convictions.

Deakin too was sometimes accused of lacking substance. He was not only a stirring platform orator, but he was quick with words in debate, and could shift positions seamlessly when the need arose. But he had core political commitments from which he never wavered. The need for a tariff to protect Australia’s manufacturers and so provide employment and living wages for Australian workers was one.

One may now disagree with this policy, but there was never any doubt that Deakin would fight for it.

Federation was another. In the early 1890s, after the collapse of the land boom and the bank crashes of the early 1890s, Deakin thought of leaving politics altogether. What kept him there was the cause of federation, and he did everything he could to bring it about.

He addressed hundreds of meetings and persuading Victoria’s majoritarian democrats that all would be wrecked if they did not compromise with the smaller states over the composition of the Senate.

Deakin had a dramatic sense of history. He knew that historical opportunities were fleeting, that the moment could pass and history move on, as it did for Australian republicans when they were outwitted by Howard in 1999.

In March 1898, the prospects for federation were not good. The politicians had finalised the Constitution that was to be put to a referendum of the people later in the year, but the prospects were not good. There was strong opposition in NSW and its premier, George Reid, was ambivalent.

In Victoria, David Syme and The Age were hostile and threatening to campaign for a “No” vote. If the referendum were lost in NSW and Victoria, federation would not be achieved.

Knowing this, Deakin made a passionate appeal to the men of the Australian Natives Association, who were holding their annual conference in Bendigo. Delivered without notes, this was the supreme oratorical feat of Deakin’s life and it turned the tide in Victoria. Although there were still hurdles to cross, Deakin’s speech saved the federation.

The second lesson Turnbull could have learnt is to have put the interests of the nation ahead of the interests of the party and the management of its internal differences.

Deakin always put his conception of the national interest before considerations of party politics or personal advantage. And he fiercely protected his independence.

He too was faced with the challenges of minority government, but it is inconceivable that he would have made a secret deal with a coalition partner to win office. Or that he would have abandoned core beliefs, such as the need for action on climate change, just to hold on to power.

As the Commonwealth’s first attorney-general, and three times prime minister, Deakin had a clear set of goals: from the legislation to establish the machinery of the new government, or the fight to persuade a parsimonious parliament to establish the High Court, to laying the foundations for independent defence, and, within the confines of imperial foreign policy, establishing the outlines of Australia’s international personality.

Party discipline and party identification were looser in the early 20th century than they were to become as Labor’s superior organisation and electoral strength forced itself on its opponents.

But as the contemporary major parties fray at the edges, and their core identities hollow out, Australians are crying out for leaders with Deakin’s clear policy commitments, and his skills in compromise and negotiation.

Had Turnbull had the courage to crash through or crash on the differences within his party on the causes we know he believes in, he too might have become a great leader and an Australian hero.

This article first appeared in The Conversation