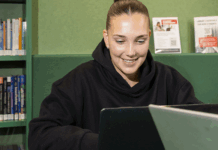

Manil Maharjan, a trained mental health counsellor from Nepal, is currently studying at La Trobe University. He hopes to use his lived experience as a visually impaired person to help people back home. We caught up with him to understand his dream.

What did you do in Nepal?

From early on, I found myself drawn to moments when someone felt heard. In Nepal, I worked with TPO Nepal, a pioneer in mental-health and psychosocial support, at the government run Mental Hospital and via the national suicide-prevention helpline. On a typical day, I might answer calls from people at their darkest hour, lead group counselling sessions, coordinate training for helpline volunteers, or run workshops for students, teachers, journalists and frontline health-workers to amplify the message that suicide is preventable.

At the same time, I taught under-graduate psychology and social work classes at Saraswati Multiple Campus in Kathmandu, sharing with young people what I’d learned about healing, hope and human connection.

What are you studying now?

Currently, I’m living in Melbourne, studying a Master’s in Rehabilitation, Counselling and Mental Health at La Trobe University under the Australia Awards Scholarship. I already hold a Master’s in Clinical Psychology from Nepal, but this new program is allowing me to deepen my knowledge around the mental-health needs of people with disabilities. As someone with vision impairment myself, this is personal. I’m not only learning how to support others but also how to build systems that include people like me.

What are the opportunities you’ve gathered here in Australia?

Being in Australia has been full of firsts and fresh perspectives. Access to La Trobe’s extensive library collections, membership in professional bodies like Australian Counselling Association and Association for Student and Graduate Organisations in Counselling (ASORC), and engagement with online courses via the Mental Health Academy have helped open doors for me.

One standout memory came through the Disability Sector Connect program. On a recent visit to Adelaide I saw how organisations championing disability rights and equal employment really function in practice. From accessible transport to adaptive gym equipment, it was an eye opener and and an example of inclusivity in action.

What are the difficulties with the disability that you have to face?

Even in this inclusive setting, I face barriers. Some components of the university’s online learning platform aren’t fully accessible to screen-reading software. I’ve raised these with teachers and the accessibility team. In the gym, some machines lack voice commands or design features that would allow me to use them independently. These may seem like small things, but for someone with vision impairment they matter. And they serve as reminders that true inclusion isn’t automatic and it requires consistent commitment and attention. I’m learning that each time I raise my voice for accessibility, I’m not just helping myself, I’m helping future students too.

What is your dream for the future?

I dream of a future where inclusivity comes naturally to all societies and nobody is disadvantaged because of their disability. My hope is to return to Nepal and apply these skills not as an outsider, but as someone who truly understands the lived experience of disability and mental-health challenges. What I’m learning at La Trobe is already making me feel more confident and capable.